Wall of Tears (Muro de las Lagrimas)

Galapagos isn’t just about wildlife, the islands have an interesting human history too. Few people know, for example, that Isabela island was once home to a penal colony. Whilst at first it seems odd to punish prisoners in paradise, the reality of prison life was very harsh. Life on a barren volcanic island was no picnic, and in order to escape inmates would have to swim over 1000km of shark-infested ocean. To make life even more unbearable, prisoners were forced to endure back-breaking manual labor. All of which brings us to the famous Galapagos Wall of Tears. Today, the wall is a national park visitor site, showcasing a very different side of Galapagos life to tourists.

Keep Reading for everything you need to know about the Wall of tears, and most importantly, how to plan the perfect visit.

SECURE YOUR GALAPAGOS TRAVEL

Get a FREE personalised quote todayWhat is the Galapagos Wall of Tears?

The Wall of Tears, or Muro de las lagrimas in Spanish, is a truly sad tale of human hardship and suffering.

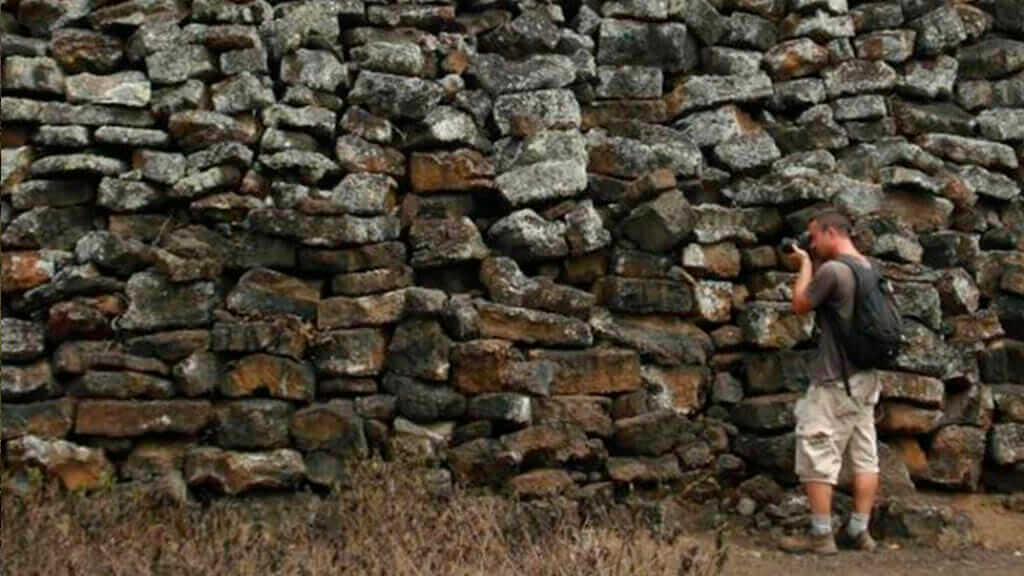

The imposing lava wall was constructed by prison inmates back in the 1940s and 1950s. Built entirely by hand, this was a labor of blood, sweat and tears. Just try to imagine, prisoners had to chisel large black lava blocks from a distant quarry, before carrying them back under a sweltering hot sun. Rinse and repeat, day in, day out, for years at a time. Working conditions were terrible; it is said that the Wall of Tears claimed thousands of prisoner lives through accidents, exposure, sickness and poor treatment.

To make matters even worse, inmates faced the unbearable psychological challenge of knowing that their labor was utterly pointless. The wall that they were building would never serve any purpose. It is literally in the middle of nowhere, seperating one area of desolate scrubland from another. It was never intended that the wall be either finished or used by anybody. Many a tough man saw his life broken by the sheer futility of the experience.

This is how the Wall of Tears received it’s appropriate name, from the crying and sacrifice of those forced to build it.

Where is the Wall of Tears in Galapagos?

The Wall of Tears is located on Isabela island, Galapagos. Isabela is the large, sea-horse shaped mass to the west of the archipelago. The wall is easily accesible, just 5km from the port town of Puerto Villamil, where most tourists overnight when visiting Isabela.

How to Visit the Wall of Tears

The best news for tourists is that the Wall of Tears is one of few Galapagos sites that can be visited without a tour guide. This makes it perfect for a cheap, flexible and easy excursion.

To visit by yourself, we highly recommend to rent a bike from one of the local agencies or hotels in town. A rough, sand & gravel path hugs the shoreline along the coast, to the west of Puerto Villamil. Biking takes around 1 hour each way. It’s easy to make a whole day of it too. There are plenty of cool spots to stop off at along the trail, from ocean lookouts to secluded beaches and mangrove forests. It’s also quite common to cross paths with a wandering giant tortoise, or other Galapagos bird species, so keep your camera handy.

The Wall of Tears site does provide basic tourist information, but it’s also possible to visit with a tour guide for those who wish to learn more. A Wall of Tears tour is easily included into a Galapagos land tour itinerary. Some Galapagos cruise routes also include a group visit to this historical site.

GET FREE ADVICE

From a Galapagos destination expert today

Is the Wall haunted?

Local legend tells that the Wall of Tears is indeed haunted by unsettled spirits. At night, it is said that one can hear the wailing cries of those who passed away during the wall’s construction.

Happy Gringo can neither confirm nor deny the legend. Neither do we recommend nocturnal visits in order to find out!

Things to do at the Wall of Tears

Ok, so in truth the site today is just a wall of lava rocks, built in the middle of nowehere. Let’s face it, this is not the most exciting place at the Galapagos Islands. But bear with us here, the Wall of Tears does have merit as a visitor site.

Firstly, in order to appreciate the wall of tears, one needs to use imagination. Put yourself in the shoes of a prisoner, on what used to be a desolate, uninhabited island. The sun beats down hard on this exposed, arid land. You’re sweating heavily, but forget about fresh water – there’s none to be found here. The black lava rocks are sharp, heavy and exhausting to carry. You’ve lost kilos of weight through lack of food and unending physical labor. Worse still, you’ve witnessed companions fall to the ground, never again to rise. Curse this damned wall!

Yes, the story is not a happy one, but it has played an important role in Isabela’s history. Look beyond the physical wall itself to understand it’s true significance.

On a lighter side, a visit to the Wall of Tears does not have to be all doom and gloom. Visitors can enjoy fine coastal views from the top of the wall’s viewpoint. There are some lovely Galapagos beaches to stop off at along the coastal trail from town. Beyond the long stretch of golden sand of Puerto Villamil’s beach, visitors soon arrive to La Playita, and then Playa del amor.

You also have the opportunity to spot some of Galapagos’ famous wildlife along the way. Passing through different arid and mangrove habitat zones, keep your eyes peeled for species like giant tortoise, lava lizard, Darwin finch, Galapagos mockingbird, marine iguana and much more.

Wall of Tears Facts

How big is the Wall of Tears?

In total the unfinished wall has dimensions of approximately 100metres long, 7metres high, and a little over 3metres wide.

When was the wall built?

The Isabela penal colony was originally established by President José María Velasco Ibarra back in the year 1944. The construction of the Wall of tears lasted from 1946 to 1959.

Why was the wall built?

This is the most pertinent question that many tourists ponder – why? The wall is completely pointless. It is just a long stretch of vertical wall that serves no purpose. It neither protects nor encloses. The sad reality is that the only true purpose of this pile of lava rocks was nothing more than to keep the prisoners busy in physical labor.

Practicalities for visiting the Wall of Tears

- 5km may not sound like a long bike ride, but a reasonable level of fitness is required to reach the Wall of tears. The path is uneven, and the heat can be draining, so don’t under-estimate this trip.

- Once the sun is up, temperatures soon become hot and sticky along the coast, especially during the warm & wet Galapagos weather season, from December through to May. Very little shade is available along the route or at the site itself. It makes sense to avoid heading out under the strong midday heat.

- Strong sun protection is a must, so go prepared with sunglasses, hat, and sunblock. Remember, even on cloudy days, white skin burns very quickly at Galapagos.

- There are no potable water sources, shops or cafés once you leave town. So, take plenty of water along with you – at least 1-2 litres, or more if you plan to bike for the whole day.

- What else to bring along? Light and comfortable clothing, energy snacks, camera / cellphone.

Want ot learn more about the human history of the Galapagos Islands? Check out our blog about the Galapagos affair - a true story of mystery and intrigue, involving the early settlers on Floreana island. Of course, a certain Charles Darwin had a rather important role to play in Galapagos history too!

Contact us to organise a Galapagos vacation that includes a visit to the Wall of tears. We’ll be happy to send you a free tour quote, with all of the very best Galapagos options for your dream trip.

Book with The #1 Trusted

Galapagos Travel Agency

In conclusion, the Wall of Tears is not your typical Galapagos visitor site. It does, however, have an important story to tell. The islands are not only about birds and animals, but also the history of early settlers long before tourists ventured to these parts. Life was far from easy for the poor prisoners of Isabela island. The Wall of tears tells their tale of struggle and hardship. A short visit here may not be your top vacation highlight, but it does give a fresh perspective of the Galapagos islands.