In Search of the Elusive Andean Bear

I have always had a big soft spot for bears. I guess it all started with my Mum’s bedtime stories of Paddington Bear adventures, and Winnie the Pooh mischief.

SECURE YOUR ECUADOR TRAVEL

Get a FREE personalised quote todayPerhaps later it developed after close encounters with various bear species on my travels: Brown, Black, Grizzly, Cinammon, Panda, Ussuri Brown, Sunbear, and even the mighty Nanook Polar bear.

So after moving to Quito, Ecuador, I naturally became curious about South America´s only native bear species – the Andean bear (or Spectacled bear), scientific name Tremarctos Ornatus. I had already visited the Cloudforest more than 10 times with no Andean bear sightings, and heard stories from seasoned guides that even they had never crossed paths with these shy and elusive creatures. So my chances of ever seeing one in the wild seemed remote, to say the least.

Fast forward more than a decade, and a chance encounter with an old friend led me to a new clue on my Andean bear quest, a clue that would lead to not just one bear sighting, but an incredible five in just one day!

Keep reading to learn more about my Ecuador Andean Bear encounter, as well as all of the Andean Bear facts and information that you ever wanted to know.

Why is the Andean Bear called the Spectacled Bear?

Before we start, let´s clear up a common misconception: What is the difference between an Andean bear and a Spectacled bear?

The short answer is that they are one and the same, with the two names often used interchangeably.

The Spectacled bear name derives from the bear’s distinctive facial markings, that makes them appear to be wearing spectacles. In fact, each and every bear has its unique markings, some with full spectacles, some half, and some with no spectacles at all.

The Andean name, of course, comes from the Andes mountain range, where these peaceful bears call home.

Where are Andean Bears found?

As the name would suggest Andean bears are found in the Andes. They mostly range from Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru & Bolivia, and occasionally even as far south as northern Argentina, or north into southern Panama.

There is estimated to be a global population of approximately 20,000 Andean bears, with 2,000 or so roaming Ecuador’s Andean forests and high paramos.

How to see Andean Bears in Ecuador?

Remember, these are very elusive and intensely shy creatures, who love to hide in dense forest. As a rule they will tend to avoid human contact.

The good news is that close to Quito there are 3 different areas where it is sometimes possible to encounter an Andean Spectacles Bear.

1. Maquipucuna lodge

Without question, Maquipucuna Lodge is the very best spot to see an Andean bear anywhere on the planet. Every year bears come to eat the ripe, wild , baby avocados (aguacatillo) in the Maquipucuna Cloud Forest Reserve. This is part of a protected, UNESCO designated Biosphere Reserve.

The incredible thing about the Maquipucuna Andean Bear-watching experience is that the chance of sightings in season are so high. Also, Andean bears are usually solitary animals, yet at Maquipucuna it is often possible to see many over a very small area. Maquipucuna bear-spotters head out into the forest early each day for tracking active bears. Their guides therefore know where to trek each day in order to find the best Andean bear action.

Bear watching season at Maquipucuna is seasonal, and a little unpredictable. The bears do come every year, but timing depends on when the aguacatillo fruits ripen. Most often this occurs sometime between September and December, but can be earlier or later. Remarkably, bears can smell the ripe fruit from over 30km away. When Maquipucuna bear season does arrive, it usually lasts between 1 and 2 months.

Contact us for up to date news about bear season. We can provide current news on whether bears are activite or not. It's possible to visit either as a day tour from Quito, or as an overnight stay at the lodge. We recommend at least a one night stay, to improve bear watching opportunities.

2. Cayambe coca ecological reserve

Cayambe Coca is a protected area of Cloud Forest and Highlands Paramo plains. This is great habitat to spot migrating Andean Bears, but more patience and luck is certainly needed here than at Maquipucuna. A 5-7day guided overnight trip is recommended to maximize your chances of bear-watching. Speak to the guide office at Papallacta Hot Springs for more information.

3. Pimampiro

Pimampiro lookout is located approximately 1 and ¼ hour drive from Ibarra Town, and is run by Project Organiser, Daniel Vasquez. It’s off of the beaten track for sure. Visitors should bring a good pair of binoculars and be prepared to settle in and wait out much of the day. Pimampiro is a year-round bear destination, although sightings are never guaranteed. More information about how to visit Pimampiro can be found at @miradordelosoandino on Facebook.

4. Chakana Reserve (Antisanilla)

Another great spot to look out for Andean Spectacled Bears is in Chakana Reserve.

With over 12,000 acres of private reserve and trails, Chakana’s pristine paramo habitat can be a great place to spot bears roaming for food. Of course, Andean bear sightings can never be guaranteed, but are quite common here.

The only way to visit is on an organized Chakana Reserve day tour from Quito. This 1-day tour is of special interest for birding, trekking, photography, and nature. Chakana is also the best spot in Ecuador to observe the Andean Condor nesting in their native habitat.

(Chakana bear photo credit - Michelle Hirbobo, permission Jocotoco)

GET FREE ADVICE

From an Ecuador destination expert todayMy Ecuador Andean Bear experience at Maquipucuna

Maquipucuna's bear season seemed like my safest bet to see an Andean bear. So, throughout 2017 I waited patiently in Quito, biding my time until I started seeing amazing bear photos on Maquipucuna’s Facebook page – bear season had arrived!

It just happened to coincide with a public holiday on the final days of the year, so I eagerly packed my kit bag and headed into the forest, as giddy as an excited schoolboy.

At the crack of dawn the next morning I was a blur of activity, scrambling out of bed, pulling on trekking gear, and shoveling down a hearty breakfast. I was in such a rush to hit the trail that I almost forgot my camera.

After half an hour of brisk walking up a gently sloping hill, with lush forest to either side, suddenly the landscape opened to our right side. We were rewarded with glorious panoramic views of the valley below, and cloud forest mountains beyond.

Most importantly though, scattered abundantly across the landscape, hundreds of wild avocado aguacatillo trees were laden with inviting ripe fruit. But, so far not a single hungry bear in sight. It was going to be a waiting game.

Around one hour later, a wave of excitement slowly filtered through the various bear enthusiasts that had assembled. We received news that a guide further up the trail had a confirmed bear sighting!

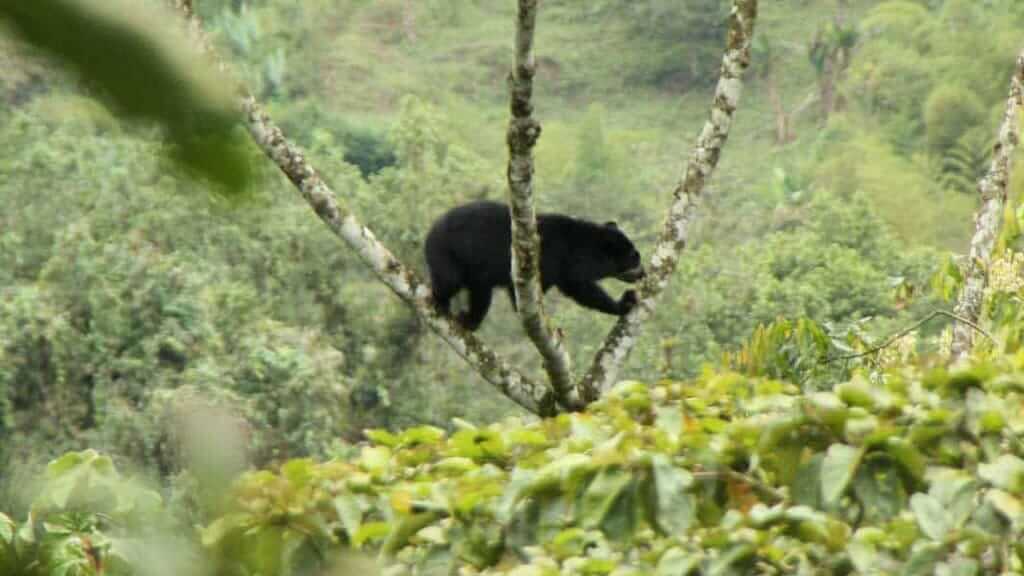

Gathering up our gear, we sprinted giddily up the trail, less than 5 minutes later meeting the guide. With a broad smile on his face, he gestured yonder into the aguacatillo trees … and there he was, an adult Andean bear, slowly climbing the trunk to reach the high-hanging fruit :)

My first impression was amazement at the agility of the bear's climb! I remember Baloo in the Jungle Book being rather on the heavy side, having to persuade Mowgli to climb for him in search of honey. In contrast, the ascent of the Andean bear before us was of slow, purposeful elegance. The tree was tall and thin, with branches that looked rather frail to support his weight, but this was clearly no problem for a dexterous bear on a determined mission.

His partial spectacle markings were clear, and he was very relaxed as he broke off fruit-laden branches, calmly munching through them. Occasionally there would be a cursory glance our way, but he seemed in no way concerned about our presence. His sole focus was clearly on getting as many small avocados fruits into his belly as possible.

A similar pattern continued throughout the morning. Guides would spot bears, we would trek further up or down the trail, and wile away happy hours watching Andean bears going about their business. The entire day on the same trail ridge brought a total of 5 bear sightings, with most staying a couple of hours up any single tree. The clear, unblocked views, and calm laziness of the bears, made photography easy, and left even the small kids in our group in silent awe.

At the end of a remarkable day, I must admit I was blown away not only by how many bears we had seen, but also how close we came to them. It was simply fascinating to stand in silence and observe their behavior. For such a shy creature, this was an unexpectedly up-close and personal wildlife experience.

My Andean bear odyssey complete, all that was left at the end of the day was to return to the lodge for a celebratory beer, and enjoy the added bonus of a lecture by esteemed Andean bear expert, Santiago Molina who also happened to be visiting Maquipucuna.

2022 Update: A second visit to see the Maquipucuna bears

Throughout October and November 2022 the bears were back! Maquipucuna is now a more popular destination for tourists - the lodge was almost full, but fortunately they managed to squeeze me in.

This time the ripe fruit was deeper in the forest, but, as always the excellent Maquipucuna bear-spotters came up trumps. Two morning treks yielded 5 bear sightings in total, and more visitors were present to enjoy this wonderful spectacle. I was also left impressed by the measures Maquipucuna go to to ensure that increased visitor numbers do not impact bear behavior.

Truly this is a unique wildlife experience, that I hope to repeat once again next time bear season rolls by.

Why is the Andean Bear endangered? And what is being done to protect bears in Ecuador?

The Andean bear is currently listed as “Vulnerable: at high risk of extinction in the wild” on the IUCN Red List of threatened species.

As with many other large mammal species, the biggest threat is caused by loss of forest habitat. In Ecuador this has largely been caused by forest clearance for agriculture and cattle farming. As their habitat has shrunk, there have also been inevitable clashes with humans, where bears are attracted to crops as a food source, and farmers see them as a threat to their livelihood.

Something had to change, and that came through Bear Ecologist, Santiago Molina, who initiated a study of bears in Pichincha Province.

His first step was to better understand the bears, so camera traps were set up to monitor more than 60 bears. This helped to estimate size and density of the Ecuador Andean bear population, their movements & interactions, as well as feeding habits. The results of this study led to the recognition of Andean Bears as an “emblematic species” by Quito Municipality.

Now that there was an agreed commitment to protect bears, the next question was how? Much debate led to a consensus to create a special ecological corridor covering 65,000 hectares, which links different zones where bears roam. The aim being to give them greater freedom of movement, and safety when they do move around. Previously bears lived in isolated National Parks & Reserves (for example Cayambe Coca, Antisana, Llanganantes, Sumaco), but faced man-made obstacles such as roads that limited their movement. Now they could enjoy greater freedom to migrate between the parks and reserves, and as a result there could be less fragmentation of the bear population. An added bonus is that the ecological corridor helps other large mammal species at the same time. The protected area of Maquipucuna also forms an integral part of the bear corridor.

Work is also being done with the local communities. Re-education to view bears positively as they attract tourists that can benefit the local community, rather than a threat to crops and livestock. More work is also needed to restrict farming and ranching in key ecological areas, to ensure better protection of Andean bear habitat.

Despite the success of bear ecology over the past decade, this work is still very much ongoing. Still far too little is known about the behavior and habits of the Andean Bear, but each passing year important new knowledge is accumulated.

Today, with growing public support and recognition of the Andean Bear in Ecuador, there is renewed hope that this shy species can be successfully protected in the future.

What do Andean Bears eat?

Andean bears are omnivores and considered the most vegetarian of all bear species. Their diet consists mostly of berries, vegetables & bromeliads, with just 5% of food beng meat such as small rodents or birds.

Are Andean Bears dangerous?

Andean bears are extremely timid, and actively avoid human encounters. They will usually run away into the forest if your paths do accidentally cross.

Only in extremely unusual situations would they ever become aggressive - if they feel threatened, or are protecting young cubs.

Do Andean Bears hibernate like other bear species?

Andean bears live in, or close to, the tropics. The warm climate produces good year-round food sources for active bears, so there is no biological need for Andean bears to hibernate like other bear species.

But, like all good bears, they do enjoy a good nap. They often sleep or rest high in the trees, where they build nests from branches, twigs & leaves. Individual Andean bears have even been observed sleeping in the same tree for several days, waiting for that tree´s fruit to ripen.

What I learned about BBC wildlife documentary making

During my 2 days at Maquipucuna, I made a rather unusual acquaintance … Bertie the BBC cameraman.

Bertie was filming as part of the BBC “seven worlds: Planet Earth III” series, and spent 2 whole months hauling heavy equipment up and down the bear trail from dawn to dusk, rain or shine.

Not only was Bertie a lovely bloke, but he was also a handy guy to follow into the forest. Where bears wandered, Bertie would follow. He inevitably found the best spots to set up his camera for optimal bear viewing, and his contagious enthusiasm kept us entertained during the bear lulls throughout the day.

I’d like to share this wonderful video with you, about Bertie's time at Maquipucuna, and the results of his hard work.

Book with The #1 Trusted

Ecuador Travel Agency

To put the life of a BBC cameraman into perspective, he led 2 long months of filming, after which his footage might be aired on TV 3 years later, or may never even see the light of day. It would all depend on the documentary editing team back in London. Even in the best case, he hoped to see only 2-3 minutes of his footage used as part of a long documentary series.

Dream job? It depends on your perspective I guess, but Bertie certainly seemed happy out in the forest each day, and I could fully appreciate his joyful passion with each new Andean bear sighting.

Written by John Potts

If you are interested in seeing Andean bears for yourself, then get in touch with me at john@happygringo.com, or complete our online form. Bears are a great passion of mine, so I will be delighted to help any other bear spotters in their quest.